Guest Editor: Brooklyn White

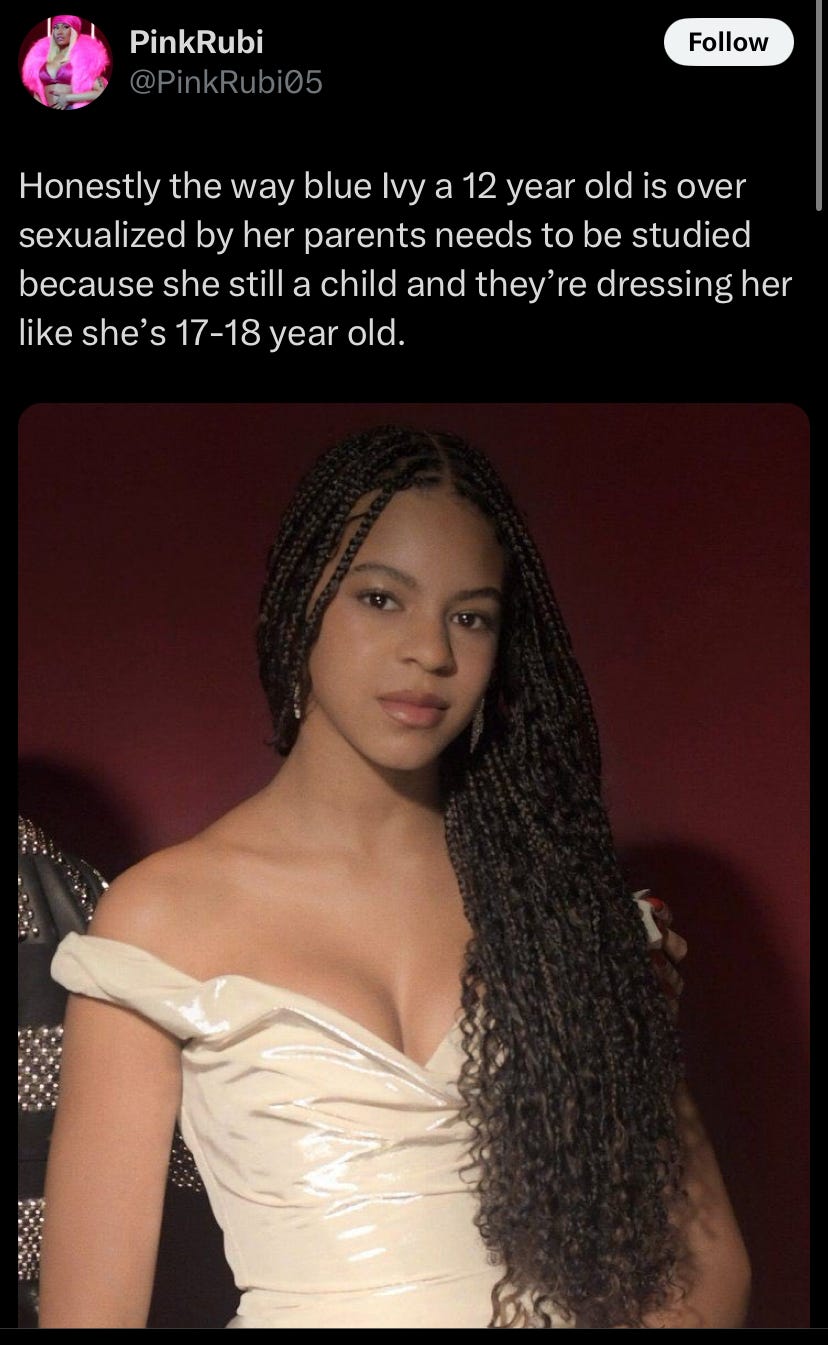

Adultification is the word of the week after the viral discourse over Blue Ivy Carter’s dress at the Mufasa: The Lion King premiere.

As with most conversations on the internet, we’ve veered off the path. We’re ignoring the implications of picking apart a child’s fashion choices and sexualizing their body.

Adultification bias is a stereotype linked to how adults perceive children and their childlike behavior. It has the greatest impact on Black girls. (According to a study conducted by Georgetown Law, participants collectively viewed that Black girls are thought to need less protection and nurturing than white girls.)

Commentary that adultifies Black girls is no longer restricted to passing strangers, educators, and family members. It has widened to the billions of people who are online. Blue Ivy is the latest and one of the most visible, victims of it.

On social media, there are no boundaries, making digital spaces constant trigger hubs for Black girls and women—whether they have online profiles or not. (In the Renaissance film, Beyoncé confirmed Blue Ivy saw the negative responses to her first performance during the pop star’s tour.) There are already unrealistic standards like body awareness, strength and maturity being placed upon Black girls as we begin puberty, which is a time that comes with clear differences across racial lines.

A 1997 study revealed that by age eight, 48% of Black girls showed signs of early onset puberty, while only 15% of their white counterparts were affected. We can’t help but see that nearly half of Black girls’ bodies are changing at a quicker pace. This time should be met with understanding.

But there is a lack of empathy regarding Black girlhood. After making snide comments, nobody thinks about how their younger sister, cousin, or mentee would respond to attacks on their body (a manifestation that is beyond their control) and beauty/fashion choices. I know not everyone has the spirit of understanding required to take in the impact of their words, but as the very definition of “girlhood” twists and adult women beg for inclusion in it, it’s important to acknowledge the ways Black girls’ adolescence is influenced by outsiders’ words and ideas.

I remember when Beyoncé revealed her pregnancy at the 2011 MTV VMA’s. It was exciting to see one of my favorite artists embark on a new chapter in her life. What I didn’t know was that I was about to see, in real-time, how adults can become so consumed with critiquing and projecting onto a child. Blogs, and even celebrities, dissected Blue Ivy’s looks, from her hair to her unquestionably Black facial features.

These viral moments, the pendulum swing towards conservatism, and the popularity of celebrity gossip platforms, have encouraged the hate Blue Ivy is getting now. Growing up, many Black girls have canon events of adultification—from being forbidden to wearing red nails because it seemed “fast” (the result of the Jezebel trope) to having their bodies inappropriately analyzed. This is racist and sexist and disallows Black girls to enjoy their youth.

I vividly remember being Blue Ivy’s age and being badgered by a teacher about how my large hoop earrings were “too much.” At the time, it felt surface-level, like maybe they didn’t like me. Now, as an adult, I can see why, and how, I was being singled out. My innocent choices led to adults making me feel like I needed to conform to more muted ways of expression when that’s not fair.

Black girls are not too grown, but they are denied the childhood they deserve. According to the Georgetown Law data, results suggest that Black girls are viewed as more adult than their white peers at almost all stages of childhood, beginning most significantly at the age of 5, peaking during the ages of 10 to 14, and continuing during the ages of 15 to 19. A teenage Black girl could be wearing a crop top or a Christian Siriano ball gown and the conversation around it will turn foul quickly. This is not true for their equals. The same culture that emulates Black girls’ speech, sense of style, and creativity relentlessly polices them.

For those who are struggling to stop speaking about a child online, think back to when you were entering your teenage years. Consider what that adolescent evolution looked like for you. You’ll come to the conclusion that Black girlhood should be protected—especially if we want to see true, lasting intergenerational camaraderie.

For Blue Ivy Carter’s 13th birthday, she deserves the gift of being able to just be.

This part makes the whole post worth reading:

“For those who are struggling to stop speaking about a child online, think back to when you were entering your teenage years. Consider what that adolescent evolution looked like for you. You’ll come to the conclusion that Black girlhood should be protected—especially if we want to see true, lasting intergenerational camaraderie.

For Blue Ivy Carter’s 13th birthday, she deserves the gift of being able to just be.”

So many of us are the little black girls who were adultified. Thank you for speaking on this.